The landmark year of 1989 was much more blurred in Karlovy Vary than elsewhere in the country. Long before the revolution, communism shook hands with capitalism here. One such case was the casino in Císařské lázně, which opened in June 1988.

The country administered by the Communist Party in the late 1980s desperately needed Western marks, shillings and dollars. Lubomír Štrougal's cabinet therefore made contacts wherever it could, and one of the results was the invitation of the Austrian developer Warimpex to cooperate with the state spa company Balnea. Together they founded the company Balnex, where the Czechoslovaks had 51% and the Austrians 49%. The aim was to invest in the spa and revitalise the spa buildings. One of the fruits of the cooperation was the Karlovy Vary casino.

Black Jack in Zander Hall

In April 1988, the Strougal government approved a "resolution on the development of the spa industry and tourism", which gave the green light to gambling in Karlovy Vary. The operation of the casino was in charge of the Czechoslovak-Austrian Balnex in cooperation with another Austrian company, Casinos Austria International. The latter supplied the roulette and black jack tables, 29 slot machines, the share capital of 1.2 million Austrian shillings and, above all, the know-how. Czechoslovakia was not the first eastern country where the Austrians headed - they had been operating a casino in Hungary since 1980.

But the domestic regime was much more constrained, and so the opening of a gambling establishment in the Zander Hall of the Imperial Spas seemed like something from another universe. The first roulette wheel was spun there on June 26, 1988, initially supposedly as a six-month experiment. In November 1988, however, the Ministry of Finance approved its permanent operation. With one major restriction. No Czechoslovak citizens were allowed inside.

Czechoslovakians banned from entering

The business was exclusively for Western visitors and passports were checked at the entrance. Czechoslovaks could only enter exceptionally as an escort for foreign guests and even then they could not play. And even if they did get in, they probably couldn't afford tea on their salaries. It cost (according to a report from 1990) an astronomical 60 CZK. For the same amount you could buy coffee, beer cost 80 CZK and a glass of Napoleon brandy 490 CZK.

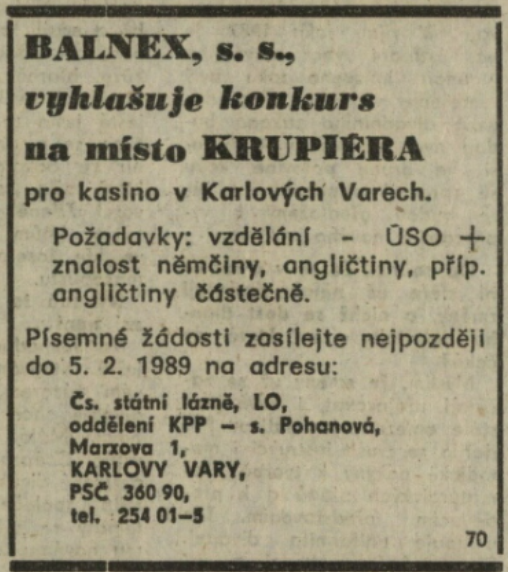

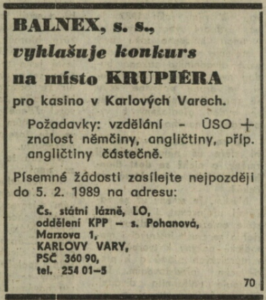

However, a select few Czechs worked in the casino. In January 1989, the communist daily Pravda ran an advertisement for croupiers. The applicants were required to have a high school or university education, knowledge of German and English and a willingness to work at night. The reward was an average salary of around 6,000 CZK per month.

Local resistance and Donald Trump

However, there was little enthusiasm for the casino among local citizens, including communists. The chairman of the Communist Party of the spa company's all-plant committee complained that the spa management did not respect the opinion of the ordinary employees, who resented the casino. The same objections were raised by the Civic Forum of Spa Employees after 1989.

After the revolution, the conditions for operation changed. After the adoption of the lottery law, even Czechoslovak citizens could play in casinos and other gambling establishments began to spring up like mushrooms after the rain all over the country. In 1994, the operation of the casino in Císařské Lázně came to an end. At that time, the building was leased from the town by a Belgian company that was planning to renovate it. The manager of the firm was quoted by the North Bohemian Daily in July 1994 as saying that Donald Trump was interested in Zander's Hall as an investor. But nothing came of the reconstruction or Trump's interest, and so only embarrassed memories of the wild 1980s and 1990s remain.

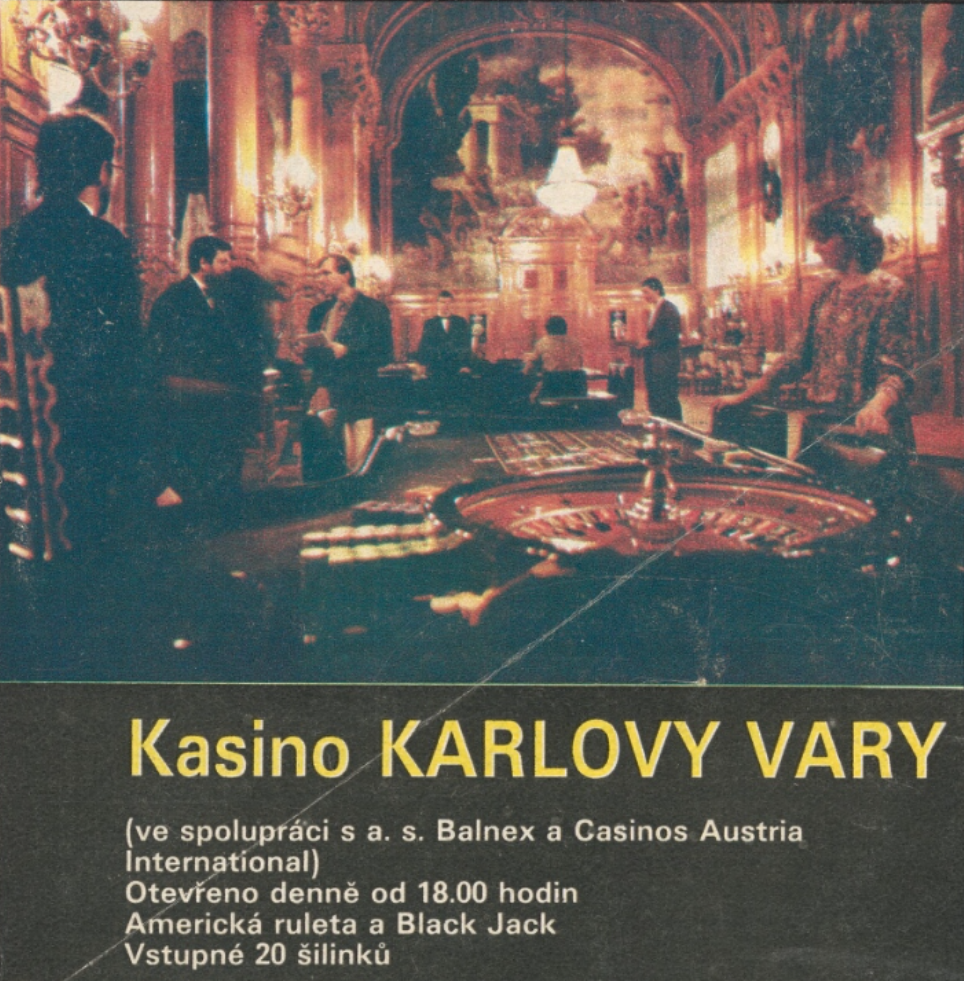

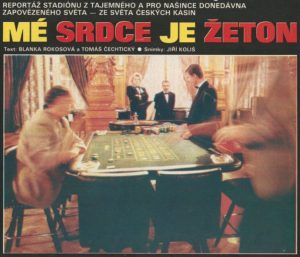

Casino advertisement in Stadion magazine, 1990

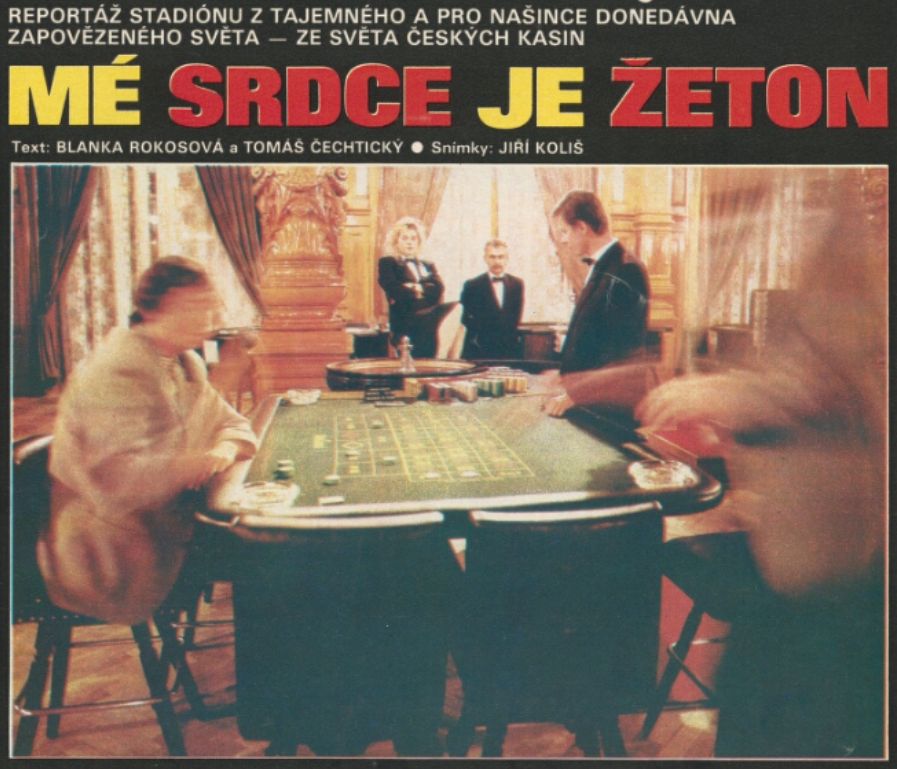

Report from Stadion magazine in December 1990. View of Zander Hall

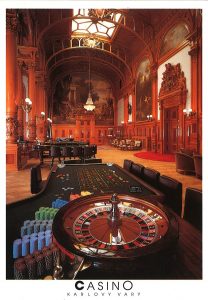

Casino in Zander Hall, Postcard from the collection of Stanislav Burachovich

Advertisement from the daily Pravda, January 18, 1989